Alejandro Sanchez-Flores, Email: alexsf@ibt.unam.mx

Agustín Lopez-Munguia, Email: agustin@ibt.unam.mx

© 2019 Sift Desk Journals. All Rights Reserved

VOLUME: 5 ISSUE: 2

Page No: 83-97

Alejandro Sanchez-Flores, Email: alexsf@ibt.unam.mx

Agustín Lopez-Munguia, Email: agustin@ibt.unam.mx

Alejandra Escobar-Zepeda1, Juan J. Montor2, Clarita Olvera2, Alejandro Sanchez-Flores1* and Agustín Lopez-Munguia2*

1Unidad Universitaria de Secuenciación Masiva y Bioinformática, Instituto de Biotecnología, Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México, Cuernavaca, Mexico

2Departamento de Ingeniería Celular y Biocatálisis, Instituto de Biotecnología, Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México, Cuernavaca, Morelos, Mexico

Escobar-Zepeda, A., Juan J. Montor, Olvera, C., Sanchez-Flores, A., López-Munguía, A., An Extended Taxonomic Profile and Metabolic Potential Analysis of Pulque Microbial Community Using Metagenomics(2020) Journal of Food Science & Technology 5(2) pp:83-97

Background: Pulque is one of the most important fermented beverages issued from the Mesoamerican past, rich in culture and tradition, as well as nutritional and physiological properties. A particular bacterial population plays a key role in the production of compounds related to pulque’s flavor and texture, as well as in its functional properties.

Methods: Using a whole metagenome sequencing approach, we characterized the bacterial population present in pulque with high taxonomic resolution so that the description is made at species level.

Results: From metagenomic information, we analyzed the potential metabolically related nutritional and sensory compounds. Species from the Sphingomonadaceae and Bartonellaceaeare family, are reorted in pulque for the first time, associated with potential probiotics. Enzymes involved in metabolic pathways of vitamins are identified, in agreement with previous reports regarding its presence in pulque. We also describe Glycosyl Hydrolase functional domains, related to the synthesis of polysaccharides, typical soluble products.

Conclusion: These results contribute to increase the knowledge of the traditional fermented products and to the history of this emblematic drink of the Mesoamerican culture.These metagenomic reservoir represents a great biotechnological potential for the food industry.

Keywords: Pulque, DNA Analysis; Enzymes; Fermentation Technology; Polysaccharides; Probiotics.

Pulque is a non-distilled traditional alcoholic beverage produced by the fermentation of the sap known as aguamiel, which is extracted from several species of Agavaceae such as Agave atrovirens and A. americana [1] . Although archaeological evidence dates back to the Otomi culture 2000 BC there is now organic evidence that this alcoholic beverage was consumed in ancient Teotihuacan since A.D. 200-550, as demonstrated by bacteriohopanoids derived from the ethanol-producing bacterium Zymomonas mobilis found in pottery vessels [2]. Aguamiel contains the carbon and energy sources from which bacteria obtain a diversity of nutrients without complementation. These substrates are composed mainly of sucrose, fructose and glucose, as well as complex sugars such as inulin and inulin-type fructooligosaccharides. Aguamiel also contains protein, free amino acids, vitamins (mainly vitamin C) and minerals [3]. For many years, the consumption of pulque has been associated to health benefits through indirect evidences related both to the plant and the resulting fermentation biomass and biomass products [4, 5]. Recently, specific health benefits have been attributed to pulque microbiota, as isolated probiotic bacterial strains have been associated to an anti-inflammatory effect in mice [6], while other properties have been inferred from the presence of specific strains [7, 8]. Therefore, there is an increasing interest in studying the microbial community involved in the fermentation of pulque. Furthermore, the description of the microorganisms and their interactions within the fermentation process to obtain pulque, is essential to maintain traditional and artisanal practices. Starter culture design, steering for sensory quality and safety improvements, is a research priority to extend the consumption of this important sustainable product. Previous efforts to identify the aguamiel fermentation associated microbiota, based on traditional microbial isolation and culturing methods, date back to the second half of last century with the pioneer work of Sanchez Marroquin and collaborators [9]. Recently, aguamiel fermentation and chemical composition studies of some agave species, have been complemented with the microbial characterization through the definition of taxonomic profiles using molecular techniques based on 16S rRNA gene amplification. These approaches have resulted in the definition of bacteria from Proteobacteria and Firmicutes phyla as well as the yeast Saccharomyces cerevisiae as the most abundant in pulque samples [10].

Additionally, a recent review describes the evolution of the main microorganisms identified in both aguamiel and pulque, in an effort to summarize the information available and define an essential microbiota responsible for pulque fermentation [11]. Nonetheless, it is well known that isolation methods based on growth in culture media restrict the identification of species present in the product, misleading real taxa richness, particularly in complex fermentation processes such as pulque. In the same context, molecular methods based on marker genes amplification, have an inherent primer bias as well as preferential amplification of the most abundant species.

For these reasons, considering that sequencing technologies are available at reasonable time and low cost, the metagenomic approach has become the most adequate strategy to explore the microbial ecology of traditional fermented foods. Whole Metagenome Shotgun (WMS) sequencing has been applied successfully in the taxonomic elucidation of microbial communities in a wide variety of lactic fermented products of vegetal origin [12, 13, 14, 15] as well as in dairy products among others [16, 17]. Additionally, sequencing technologies fulfil the need to assess the microbial risk of food through a highly sensitive level, and the use of WMS approaches over 16S rRNA taxonomic profiling present several advantages. Therefore, a screening methodology to characterize the microbial communities during production regarding the safeness of the final product, is very convenient [18, 19, 20] .

In this study, we describe the bacterial microbial community involved in the pulque fermentation process from a taxonomic and functional point of view, using DNA sequencing technologies that provide information with higher resolution than classical microbiology and molecular biology methods previously employed. To our knowledge, this is the first study that integrates both taxonomic and functional information, to corroborate and extend previous findings regarding this traditional alcoholic beverage, with a growing economic and social interest within the Mexican society and the traditional food sector.

2.1. Collection of pulque samples

Homemade pulque was collected from Huitzilac, Morelos, México, a cold weather mountainous region, in August, 2013. The town is located in the globe coordinates: 19.028333 N and 99.267222 W, at 2,561 m above sea level. The average temperature in this region is ~20°C in summer. In accordance with traditional procedures, pulque was prepared by a local supplier from fresh aguamiel by means of a batch-fed production system. Fermentation takes place in a vessel known as tinacal, in which fresh aguamiel is added twice a day allowing the fermentation to develop naturally from 3 to 6h, but overnight or even extended periods of one or two days are not uncommon. One liter of 24 and 48h pulque samples were collected in a sterile glass container, transported to the laboratory in ice to slow the fermentation and processed the same day. The pH of both samples was 4.0 which is consistent with previous reports [21].

2.2. Metagenomic DNA extraction

In order to obtain an overall view of the bacterial microbial community involved in the fermentation both 24 and 48 h fermented pulque samples were mixed and centrifuged 30 min at 4000 rpm to remove yeast cells, and then 20 min at 8000 rpm to collect the microbial population enriched in prokaryotes. Total DNA extraction was performed with the UltraClean Microbial DNA isolation kit (MoBio, cat. 12224-250) following provider instructions. The integrity and quantity of the extracted DNA were evaluated in 0.8% agarose gel electrophoresis and by NanoDrop. Total DNA was precipitated overnight with absolute ethanol (1:1 v/v) at -20°C and the pellet was dissolved with sterile tetra-distilled water at a final concentration of 100 ng/μl.

2.3. Library preparation, sequencing and bioinformatic analysis of data

An Illumina library was prepared from total DNA using the TruSeq DNA kit (Illumina, USA) following the manufacturer's specifications with an average fragment size of 200-400 bp. The sequencing was performed on the GAIIx (Illumina, USA) platform with a paired-end 72-cycle configuration at the “Unidad Universitaria de Secuenciación Masiva y Bioinformática” (UUSMB) of the “Instituto de Biotecnología”, UNAM, Mexico. The sequencing data related to this work is available at the NCBI Bioproject under the ID PRJNA506993.

The quality control of the reads, previously cleaned from adapter sequences, was carried out using the FastQC software (http://www.bioinformatics.babraham.ac.uk). The Parallel-Meta pipeline v2.4.1 [22] was used to assess the taxonomic labelling based on 16S rRNA marker genes using the RDP 16S rRNA database as reference, using the default parameters. The taxa count table obtained from Parallel-Meta was used to compute the sampling effort by Vegan v2.3.0 [23] and the diversity indices were estimated by phyloseq v1.12.2 [24], both from the Bioconductor R packages. The Good’s coverage was calculated using a Perl script. An additional taxonomic annotation based on k-mer spectra was performed in order to obtain the microbial community characterization at species level. For this purpose, we used the Kraken v1.0 software [25].

The reconstruction of genomic fragments was performed by de novo assembly using IDBA-UD v1.1.1 [26] with the default parameters, and the Open Reading Frame (ORF) sequences were predicted by MetaGeneMark v2.10 [27] software from the contigs of size larger than 200 bp. The translated sequences annotation was carried out using Blast v2.2.30+ algorithm [28] against UniProtKB/Swiss-Prot database (UniProt Consortium, 2018). Additionally, a functional domain annotation was performed using the hmmscan tool from HMMER v3.1b1 [29] suite to search against the PFAM-A database [30]. Finally, the annotation outputs were integrated by an adaptation of the Trinotate v2.0.1 pipeline [31]. In parallel, we submitted the ORF translated sequences to the GhostKoala v2.0 [32] annotator for metabolic pathway reconstruction against the KEGG database [33].

2.4. Screening of enzymes potentially related with the production of sensorial and nutritional compounds

The production of nutritional and flavor molecules was predicted by identification of genes corresponding to the metabolic pathways of interest, as well as searching for specific enzymatic annotation of reactions reported in the literature related to polymers and oligosaccharides formation. Enzymes related with prebiotic properties of pulque were identified using PFAM annotation. A detailed analysis of glycosyltransferases, glycosidases and other carbohydrate active enzymes (CAZY) were performed based on domain analyses, structure and catalytic residues. Enzyme domain identification was performed employing the NCBI Conserved Domains searcher [34], while the prediction of enzyme active sites and structure were made using the I-TASSER server [35].

3.1. General stats and taxonomic diversity in pulque

The sequencing results showed that the Phred score quality average remained above 30 in all positions on both set of paired reads, reflecting a high-quality sequencing procedure. A summary of the statistics of sequencing, assembly and annotation results are shown in Table 1.

Table 1. Basic statistics of sequencing and bioinformatic analysis of pulque taxonomic diversity

|

Sequencing |

|

|

Total number of reads |

49,720,874 |

|

Total bases (Gb) |

3.69 |

|

Assembly |

|

|

Number of total bases in the assembly (Mb) |

24.6 |

|

Number of assembled reads (%) |

47,966,386 (96.48%) |

|

Number of total contigs |

22,046 |

|

Average size of contigs (bp) |

1,115 |

|

Longest contig size (bp) |

168,915 |

|

Shortest contig size (bp) |

200 |

|

N50 / N90 (bp) |

2,710 / 354 |

|

Functional Annotation |

|

|

Total of predicted Open Reading Frames (ORFs) |

38,612 |

|

ORFs with PFAM annotation |

22,024 |

|

ORFs with BLAST/Swiss-Prot db annotation |

19,637 |

|

ORFs with K number assigned by GhostKoala |

14,269 |

|

16S rRNA reads extracted by Parallel-meta |

151,789 |

Regarding the taxonomic annotation, Parallel-Meta reconstructed a total of 151,789 ribosomal fragments (Table 1), from which 118,229 (~78%) were mapped to a reference sequence in the RDP database and classified them in 391 taxa corresponding to Bacteria domain. Using ribosomal genes as phylogenetic marker, genus level was the highest resolution achieved in the taxonomic assignment. According to Chao1 richness estimator, the number of expected taxa was ~549, indicating a sampling effort of ~71%. Other estimators such as ACE, Shannon (Hs) and Simpson (1-D), reported values of 580.51, 2.79 and 0.84, respectively. Additionally, the Good’s coverage for this sample was estimated in 0.999982.

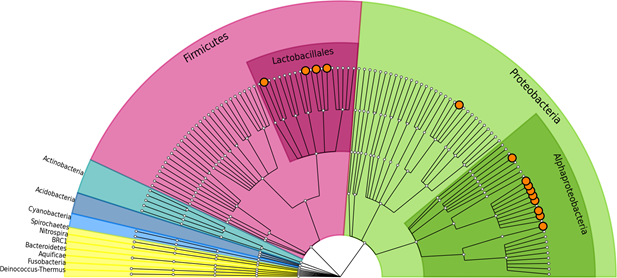

The bacterial community of pulque is composed mainly by Proteobacteria (~70% in relative abundance), and Firmicutes (~28%). Some other minority groups were found in abundance lower than 1% corresponding to Cyanobacteria, Actinobacteria, Fusobacteria, Acidobacteria and Nitrospira phyla (Figure 1).

The most abundant genus in the pulque bacterial community was Zymomonas, representing almost 36% of the total relative abundance. Following Zymomonas in abundance, thirteen genera from Proteobacteria and Firmicutes phyla, with more than 1% of total relative abundance, are shown in Table 2 and highlighted with orange dots in Figure 1. From these thirteen subdominant genera, we found eight of them not reported previously neither by molecular nor by culture isolation techniques in pulque samples.

Figure 1. Taxonomy cladogram of bacterial assigned taxa with >10 ribosomal metagenomic reads. Genera representing >1% of total relative abundance, are highlighted with orange clade markers. The highest richness is observed in Proteobacteria and Firmicutes phyla.

Table 2. Annotation table and total relative abundance of the most abundant bacteria (by phyla) in pulque microbial community (abundance <=1%). Genera described for the first time in pulque are depicted in bold.

Among detected phylotypes with a relative abundance of less than 1% and represented by more than ten metagenomic reads, we found up to 250 different bacteria comprised in 12 phyla. Most of the genera presented in this rare biosphere group, have not been reported in pulque samples before. (Supplementary Table 1).

Using the taxonomic annotation results from Kraken at species level resolution (see Methods and Supplementary Table 1), we performed a screening of the main foodborne pathogens [36]. Species such as Staphylococcus aureus, Listeria monocitogenes, Vibrio cholerae, Brucella spp., and Campylobacter spp were not detected. Nevertheless, some annotated sequences belonging to other pathogens were found in very low proportions: Pseudomonas aeruginosa (0.00064%), Salmonella enterica (0.00086%) and Yersinia spp. (0.00169%). Coliform bacteria group, which is commonly used as an indicator of microbiological quality in food, was detected as well, but also at extremely low relative abundance: Klebsiella spp. (0.00254%), Citrobacter spp. (0.00085%), Serratia spp. (0.02537%), Enterobacter spp. (0.00085%) and Escherichia coli (0.00677%). Similarly, other potential pathogens present in the oral cavity, such as Streptococcus mutans 0.002895% and Streptococcus salivarius 0.000006% were detected in low abundance. This confirms previous results [21] which suggest a low risk for consumers after demonstrating that pathogenic strains introduced in pulque, including Salmonella, are not present in the final product [37]. Conversely, reads annotated as Lactobacillus sanfranciscensis, which has been associated to an anti-inflammatory effect in mice [6], were found with a relative abundance of 0.412494%. We also found L. mesenteroides and L. casei with a relative abundance of 0.042690 and .0062776%,respectively.

Although the DNA isolation procedure was optimized for bacteria, we found very few reads annotated as eukaryotes. Those reads were mainly assigned to mitochondrial DNA from organisms of Liliopsida class level, where agave is classified. Also, reads annotated as organisms belonging to invertebrates like nematodes and fungi were found in very low abundance (< 0.00001%), in particular, reads annotated within the Saccharomycetaceae family.

3.2. Screening of enzymes related to nutritional and sensory compounds associated to pulque

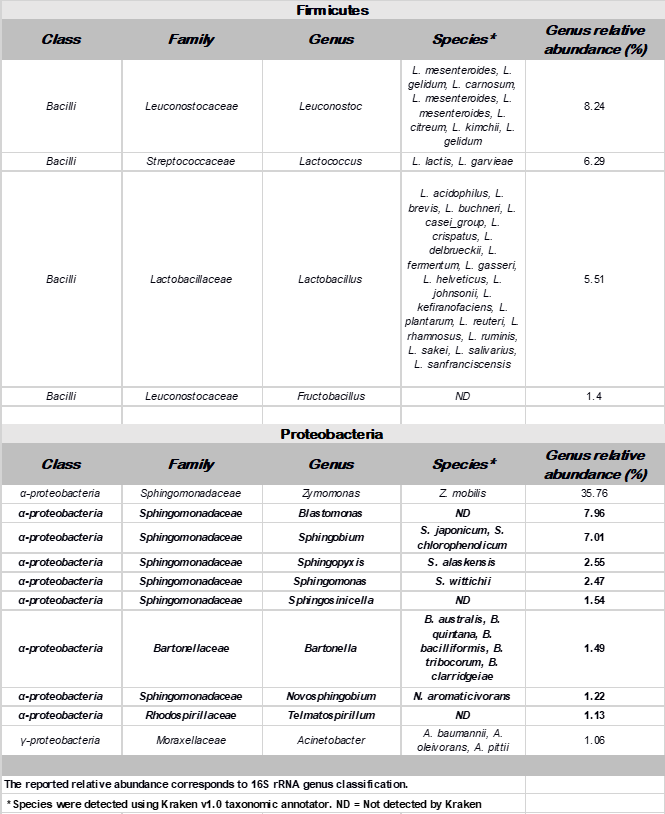

From the predicted and annotated ORFs, we identified several enzymes involved in the production of compounds related to pulque’s nutritional and sensory properties (Table 3). We were able to identify enzymes implicated in the synthesis reaction of virtually each vitamin previously reported in pulque. Interestingly, we found enzymes related with the cobalamin and folic acid synthesis, even though the presence of these compounds has never been reported in pulque. Additionally, we found the complete enzymatic pathway needed for lactic acid and most abundant sugars and polysaccharide metabolism in pulque (levan, dextran and sucrose), represented in both, Firmicutes where most abundant genera in pulque are Leuconostoc, Lactococcus and Lactobacillus and Alphaproteobacteria (mainly Zymomonas). Enzymes related with the synthesis of ethanol, acetaldehyde and acetate mainly by Alphaproteobacteria, were also observed (Figure 2).

Figure 2. Metabolic reconstruction of KEGG modules related with starch and sucrose metabolism and glycolysis/gluconeogenesis. EC numbers of enzymes detected in Firmicutes phylum are filled in purple; EC numbers of enzymes corresponding to Alphaproteobacteria are highlighted in orange. The metabolic pathway steps represented mainly in the mentioned taxonomic groups, are framed following the described color code.

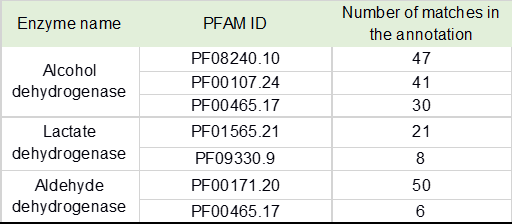

We complemented the screening strategy for enzymatic activities involved in the alcoholic and acid fermentation, using a PFAM annotation analysis. This analysis allowed the detection of enzymes containing functional domains characteristic of alcohol dehydrogenase, lactate dehydrogenase, and aldehyde dehydrogenase and the frequency of these enzymes in the microbial community, as shown in Table 3.

Table 3. Enzymes and reactions related to metabolic compounds commonly associated to pulque (GhostKoala annotation). Matches with related genes in the metagenome.

|

Reaction |

Enzyme name |

Enzyme EC number |

Matches* |

Reference |

|

Vitamins |

||||

|

ATP + thiamine phosphate <=> ADP + thiamine diphosphate |

Thiamine phosphate kinase |

2.7.4.16 |

4 |

|

|

|

||||

|

Dethiobiotin + sulfur-(sulfur carrier) + 2 S-adenosyl-L-methionine + 2 reduced [2Fe-2S] ferredoxin <=> biotin + (sulfur carrier) + 2 L-methionine + 2 5'-deoxyadenosine + 2 oxidized [2Fe-2S] ferredoxin |

Biotin synthase |

2.8.1.6 |

6 |

|

|

N-((R)-4'-phosphopantothenoyl)-L-cysteine<=> pantotheine 4'-phosphate + CO2 |

Phosphopantothenoylcysteine decarboxylase |

4.1.1.36 |

12 |

|

|

|

||||

|

ATP + pyridoxal <=> ADP + pyridoxal 5'-phosphate |

Pyridoxal kinase |

2.7.1.35 |

4 |

|

|

|

||||

|

2 6,7-dimethyl-8-(1-D-ribityl)lumazine <=> riboflavin + 4-(1-D-ribitylamino)-5-amino-2,6-dihydroxypyrimidine |

Riboflavin synthase |

2.5.1.9 |

10 |

|

|

|

||||

|

5,6,7,8-tetrahydrofolate + NADP+ |

Dihydrofolate reductase |

1.5.1.3 |

8 |

|

|

<=> 7,8-dihydrofolate + NADPH |

|

|||

|

Adenosylcobinamide-GDP + alpha-ribazole <=> GMP + adenosylcobalamin |

Cobalamin synthase |

2.7.8.26 |

3 |

|

|

|

||||

|

Alcohols |

||||

|

An alcohol + NAD+ <=> an aldehyde or ketone + NADH |

Alcohol dehydrogenase |

27 |

||

|

1.1.1.1 |

||||

|

Lactate |

||||

|

Lactate + NAD+ <=> pyruvate + NADH |

Lactate dehydrogenase |

1.1.1.28 |

29 |

|

|

Acetate |

||||

|

Aldehyde + NAD+ + H2O <=> Carboxylate + NADH |

Aldehyde dehydrogenase (NAD+) |

1.2.1.3 |

2 |

|

|

Polymers |

||||

|

Sucrose + (2->1 o 2->6)-β-D-fructosyl(n) <=> |

Fructansucrase |

|

||

|

glucose + (2->1 o 2->6)-β-D-fructosyl (n+1) |

2.4.1.10/ 2.4.1.9 |

28 |

||

|

|

|

|

||

|

Sugars |

||||

|

Reaction |

Enzyme name |

Enzyme EC number |

Matches* |

References |

|

Levan + H2O <=> Levanbiose |

Fructanase |

3.2.1.65 |

3 |

|

|

Dextran + H2O <=> Isomaltose |

Dextranase |

3.2.1.11 |

4 |

|

|

Sucrose + H2O <=> D-Fructose + D-Glucose |

β-fructofuranosidase |

3.2.1.26 |

7 |

|

3.3. Screening of enzymes related with soluble fiber and potential prebiotic compounds

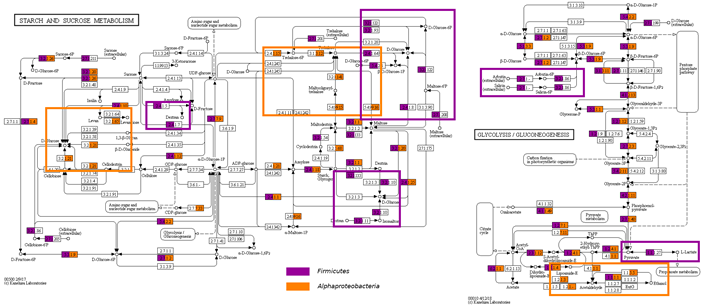

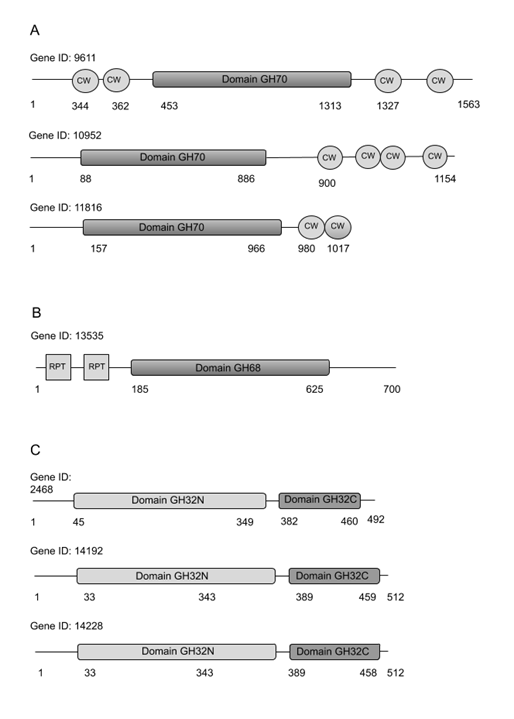

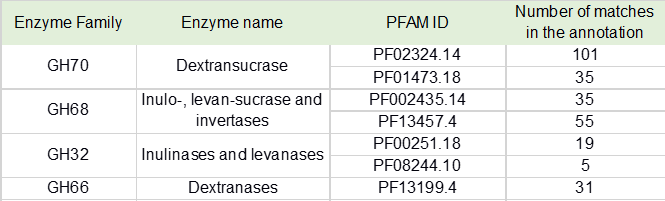

One of the most important nutritional properties associated to pulque, besides the wide diversity of the here described lactic acid bacteria is the presence of soluble fiber. It is indeed one of the major concerns of the differences between the modern and the so called “traditional diet”, calling for an increased consumption of complex carbohydrates [38]. In this context, pulque has always been distinguished by its viscous texture associated to the synthesis of complex sugars, the result of a so called “viscous fermentation” and now clearly associated to the enzymatic synthesis of dextran, levan and inulin. For this reason, the same manual screening approach for functional domain annotation was applied to detect important enzymes involved in polysaccharides metabolism. These results are shown in Table 5 where the number of matches for enzyme families GH70 (dextransucrases), GH68 (levansucrases, inulosucrases and β-fructofuranosidases), GH32 (invertases, inulinases, and levanases); GH66 (dextranases), are shown in Table 5. We also performed a domain architecture analysis for these enzymes which is depicted in Figure 3.

Figure 3 Structural representation of coding sequences for the glycoside hydrolase enzyme domains detected in the pulque bacterial metagenome A) Gene products containing the family GH70 and Cell Wall Binding (CW) domains. B) Gene products containing the family GH68 and repeated (RPT) domains C) Gene products containing the family GH32 amino and C-te

3.4. Taxonomical characterization of pulque bacterial consortium and its role in pulque fermentation

Pulque is an iconic traditional artisanal beverage of Mexican culture with no standard procedure for the microbial fermentation process. Previous efforts using classic microbiology and molecular biology techniques to characterize the bacteria population directly involved in the fermentation process, resulted in an important but incomplete microbial profile. Therefore, the use of a whole metagenome shotgun approach can retrieve a complete bacterial taxonomic profile and to define the metabolic potential within this microbial community. For instance, the presence of lactic acid bacteria in pulque has an important role in the exopolysaccharide synthesis, which is performed mainly by Leuconostoc species, as well as in the lactic acid fermentation by Lactococcus and Lactobacillus genera that have been already been described [11]. In this context, our results are consistent with previous findings but now offer a wider and novel perspective. As an example, Sphingomonas, Sphingobium, Novosphingobium, and Sphingopyxis are part of a closely related genera, detected for the first time in this work. This group represents around 13% of the relative abundance of the bacterial community, and include bacteria species that have been described as strictly aerobic, chemoorganotrophic, and rod-shaped, containing glycosphingolipids (GSLs) as cell envelope components. Species from these genera are commonly isolated from sediments, soil or associated to plant roots [39]. Therefore, their presence in pulque could be related to the origin of the aguamiel, but also to the aguamiel extraction procedure (usually mouth suction), as some oral taxon of Sphingomonas have been reported as transient species in human saliva samples [40]. From a metabolic perspective, despite being highly abundant in pulque, it is unlikely that this group contributes significantly to the production of lactate, ethanol or acetate as all of them are negative to glucose fermentation. Nonetheless, this group of bacteria is metabolically versatile, and some species have particular and alternative pathways for carbohydrate metabolism [41]. Finally, its prevalence during fermentation could be associated to a non-reported tolerance to ethanol. However, further studies are needed to elucidate their role in pulque fermentation or its frequency and importance among the microbial community.

Regarding the safeness of the final product, our results indicated an extremely low abundance of DNA related to pathogens, strongly suggesting that these are excluded during the fermentation process, must probably due to the bacterial community dynamics. This confirms that the final product is safe for consumption. Interestingly, we corroborate the presence of Lactobacillus sanfranciscensis, and L. mesenteroides, both with demonstrated probiotic properties, the former reported as a strain associated to anti-inflammatory effects in mice [6, 42]. Although it is not abundant in the studied sample and we didn’t verify if the detected species was the same as the reported strain, this is an interesting result that could lead to the detection and isolation of new probiotic strains of the same or different species. The production of bacteriocins, and other gut-brain related metabolites have also been reported for strains of L. mesenteroides, L. citreum, L. brevis, etc. Actually, recent reports suggest a decreased stress behavior in mouse after treatment with L. rhamnosus, also found in pulque, and already known as a probiotic influencing the immune system [43].

3.5. The metabolic potential of the microbial community, related to nutritional compounds and sensory features in pulque

The most important alcohol producer strains in pulque are S. cerevisiae and Z. mobilis [44]. Considering that high reducing sugars concentration found in aguamiel (>15% w/v) inhibit S. cerevisiae growth, initial conditions favor Z. mobilis activity. Scopes et al [45] pointed out that Z. mobilis through the Entner-Doudoroff pathway is capable to carry out a rapid glucose conversion to ethanol. It is also known that S. cerevisiae cells have a weak osmo-tolerance, performing a more efficient alcoholic fermentation once sugar concentration has been reduced to less than 15% w/v [46]. In experiments performed with single isolated strains, it has been observed that Z. mobilis may produce up to 8 mg/ml of ethanol, while S. cerevisiae produce 5 mg/ml under the same initial sugar concentration [4]. It is also know that although Z. mobilis is less resistant to ethanol concentration, has a higher specific production rate. This may explain why Z. mobilis could have an important role as alcohol producer in pulque.

In general, the functional inference resulting from data association based on sequence identity, structure analogy and Hidden Markov Models built from curated references, give us higher confidence about the annotated enzymes and their agreement with previous reports for metabolic pathways and enzymatic activities reported for pulque. Sequences annotated as alcohol dehydrogenase with PFAM ID: PF00465.17 (iron-containing alcohol dehydrogenase iron-containing, Table 4), have been identified in yeast and in Zymomonas mobilis. [49]. These alcohol dehydrogenases are strongly related with the propanediol oxidoreductase from E. coli, the NAD dependent 4-hydroxybutirate dehydrogenase from Clostridium acetobutylicum and C. kluyveri, the 1-3 propanediol dehydrogenase from Citrobacter freundii, and the NAD-dependent methanol dehydrogenase from Bacillus methanolicus according this PFAM family members description.

Table 4. Enzymes with domains related to acid and alcoholic fermentation found in pulque’s metagenome according to PFAM annotation.

Table 5. Functional domain analysis of prebiotic soluble fiber synthesis and hydrolysis enzymes detected in the pulque bacterial metagenome

3.6. Metabolic potential for vitamin production in pulque metagenome

In addition to simple sugars such as sucrose, glucose and fructose, a wide variety of polysaccharides such as fructans (inulins and levans) and glucans (dextrans) are part of the diversity of carbon sources either produced or available for microbial growth in pulque [11]. As already mentioned, such polysaccharides, have proven prebiotic capacity [49, 50] are responsible for the distinctive viscous texture of the beverage and have been associated to its nutritional properties [3]. Vitamins are also associated to the high nutritional quality of pulque, particularly vitamin C, thiamine, pantothenic acid, niacin, biotin and riboflavin [9]. On the other hand, compounds such as alcohols, organic acids and free amino acids, together with particularly ethanol, lactic and acetic acid are strongly related to the characteristic flavor and aroma of the beverage.

Although folic acid and cobalamin have not been directly reported or found in pulque [51], it is known that some of the main bacterial producers of these vitamins, as Bifidobacteria (B. bifidum, or B.longum sub. infantis), Lactobacillus, and Saccharomyces [52] are commonly found in pulque. As only bacteria and archaea contain the required enzymes and metabolic pathway to synthesize cobalamin, foods serve as source of this vitamin due to the presence of such bacteria [53]. Among cobalamin producers it is worth mentioning Propionibacterium freudenreichii and L. reuteri [54]. Through reconstructions of pulque’s bacteria metabolic pathways, enzymes involved in cobalamin synthesis were identified in pulque’s metagenome. Also, Bifidobacterium and Lactobacillus were detected in relative abundance of 0.06 and 5.51% respectively in pulque metagenome.

Vitamin C has been reported as a nutritional component of pulque [55]. However, the metabolic pathway required for the synthesis of this vitamin is poorly represented in the metagenome, so its presence maybe directly associated to aguamiel, as only plants and a small group of microorganisms such as Acetobacter suboxydans, Chlorella pyrenoidosa, Candida norvegensis, and Aspergillus possess the genetic machinery necessary for the production of this vitamin. In the bacterial community of pulque, the population of Acetobacter is found in relative abundance of ~0.12%. Furthermore, Acetobacter is responsible for pulque spoilage due to acetic fermentation [56]. It is therefore adequate to conclude that Vitamin C derives from aguamiel, as reported decades ago by Cravioto et al, who found that pulque contains around 6.2 mg but aguamiel twice that amount [57].

3.7. Functional domain arrangement in the glycoside hydrolases of pulque metagenome

As mentioned before, the manual screening of functional domain annotation allowed the identification of sequences coding for enzyme families relevant in sugar polymers metabolism, especially in cases where a more detailed annotation was necessary or GhostKoala annotation was not very descriptive. This was the case of the GH70 family enzymes, where dextransucrases were corroborated manually. Also, we found sequences coding for enzymes belonging to families GH68 (levansucrases, inulosucrases and β-fructofuranosidase), GH32 (invertases, inulinases, and levanases) and GH66 (dextranases). Some of these enzymes could be involved in the hydrolysis of agave’s inulin (GH32), while some others (GH68 and GH70) in the synthesis of fructans and glucans from sucrose during aguamiel fermentation. Some of the hydrolytic enzymes (GH32 and G66) may also be active at the end of the fermentation, reducing the characteristic viscosity associated to pulque. Interestingly, we observed a particular domain arrangement in the coding sequences related with the prebiotic compound synthesis, found in the pulque metagenome. From the total sequences identified as glycosyltransferases belonging to family GH70, only three (Gen ID: 11816, Gen ID: 10952; Gen ID: 9611) contained the entire catalytic domain, with two or more cell wall binding (CW) domains (Figure 3A), characteristic of enzymes from lactic acid bacteria as Leuconostoc mesenteroides commonly associated to pulque (Table 2). A particular GH70 dextransucrase producing a high viscosity polysaccharide was produced from a L. mesenteroides strain isolated from a pulque [58].

Using the BlastP program for a more detailed annotation, a sequence comparison against the non-redundant protein database resulted in a 91% identity match of Gen:11816 with the glucansucrase from Lactobacillus parabuchneri (AAU08006.1); while the sequence of Gen ID: 10952 resulted with 69% identity match with the enzyme from Lactobacillus sakei (AAU08011.1), a species observed in this work (Table 2). Finally, Gen ID:9611 has 96% identity with the glucansucrase described as an alternansucrase [59]. In addition, in the comparison against the SwissProt database, the Gen ID:11816, Gen ID: 10952 and Gen ID: 9611 were found to have 52, 48 y 47% identity respectively with a glucansucrase from Streptococcus mutans, a strain observed in a very low abundance in this work.

Among the sequences coding for enzymes of family GH68, only the Gen ID: 13535 showed the entire catalytic domain. This sequence presents a 74% identity with the fructansucrase known as inulosucrase (IslA) from Leuconostoc citreum (AAO25086.1) [60]. The main differences between Gen: 13535 and IslA sequence are located in the N-terminal region, the former having a 109 aminoacids shorter N-terminal region. Nonetheless, Gen: 13535 shares with IslA the two repeat modules RPT, and lacks the cellular membrane associated domains (SH3 domains) in the C Terminal region (Figure 3B).

From the coding sequences of enzymes belonging to family GH32, only the Gen ID: 14192, Gen ID: 14228 and Gen ID: 2468 preserve the complete conserved domains (Figure 3C). Sequences of the Gen ID: 14192 and Gen: 14228, had 81 and 99% identity with invertase from Zymomonas mobilis (F8DVG5.1), respectively, and 49% identity with an invertase from Streptococcus mutans (P13522.3). It is important to point out that Gen ID: 14192 and Gen ID: 14228 sequences have an 80% identity in aminoacid sequence. Finally, the analysis of the conserved domains of the coding sequences of enzymes from family GH66, allowed us to conclude that none of the enzymes has a complete GH66 domain.

Metagenomics has proven to be a very effective approach to study microbial communities from very different sources and fermented food products are not the exception. This study not only confirms previous results but also extends the knowledge regarding the taxonomic profile and metabolic potential found in the pulque microbiota. Despite differences between pulque samples and fermentation processes reported by other authors, our findings are very consistent at a global taxonomic level. Our results confirm at very high resolution, that this traditional artisanal beverage has virtually null presence of DNA from pathogens, the main concern related to artisanal food products. We also confirmed the presence of previously reported isolated probiotic bacterial strains associated to anti-inflammatory properties. These results could lead to the isolation of other strains with similar or new probiotic properties.

The metabolic potential inferred from the genetic information from the pulque microbiota, reflects a very wide and complete metabolism where important nutrients can be produced. These results can improve and help the food biotechnology area, where a plethora of enzymes for synthesis and degradation of sugar polymers could be characterized. The number of enzymes with different metabolic and catalytic activities related to soluble fiber or carbohydrate polymers synthesis, are a valuable information repository to guide experiments where reactions can be performed by enzymes with potential of more efficient catalytic rates, recognition of different substrates or synthesis of novel products. Finally, we consider that our results can transcend to a social level where this traditional drink has a historical importance within the Mexican culture.

We would like to thank the “Unidad Universitaria de Secuenciación Masiva y Bioinformática” (UUSMB) of the Instituto de Biotecnología, UNAM, for advice on DNA sequencing and bioinformatic analysis. The UUSMB is part of the “Laboratorio Nacional de Apoyo a las Tecnologías en Ciencias Genómicas” which was created and funded by the Programa de Laboratorios Nacionales CONACyT #260481. We also thank Fernando Gonzalez Muñoz and Maria Elena Rodriguez Alegría for technical and field support.

Authors contributions

AEZ and ASF performed the taxonomic profiling, functional annotation and metabolic bioinformatics analyses and drafted the manuscript; CO supervised and performed the required experiments; JJM performed the manual screening of the protein domain architecture and part of the metabolite analysis; ALM conceived and coordinated the project. ALM and ASF wrote the manuscript.

Author Declaration

We wish to confirm that there are no known conflicts of interest associated with this publication and there has been no significant financial support for this work that could have influenced its outcome.

Escalante, A., Giles-Gómez, M., Hernández, G., Córdova-Aguilar, M.S., López-Munguía, A., Gosset, G., Bolívar, F., 2008. Analysis of bacterial community during the fermentation of pulque, a traditional Mexican alcoholic beverage, using a polyphasic approach. Int. J. Food Microbiol. 124, 126-134. PMid:18450312

View Article PubMed/NCBICorrea-Ascencio, M., Robertson, I.G., Cabrera-Cortés, O., Cabrera-Castro, R., Evershed, R.P., 2014. Pulque production from fermented agave sap as a dietary supplement in Prehispanic Mesoamerica. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 111, 14223-14228. PMid:25225408

View Article PubMed/NCBIOrtiz-Basurto, R.I., Pourcelly, G., Doco, T., Williams, P., Dornier, M., Belleville, M.-P., 2008. Analysis of the main components of the aguamiel produced by the maguey-pulquero (Agave mapisaga) throughout the harvest period. J. Agric. Food Chem. 56, 3682-3687. PMid:18433106

View Article PubMed/NCBIBackstrand, J.R., Allen, L.H., Martinez, E., Pelto, G.H., 2001. Maternal consumption of pulque, a traditional central Mexican alcoholic beverage: relationships to infant growth and development. Public Health Nutr. 4, 883-891. PMid:11527512

View Article PubMed/NCBIBackstrand, J.R., Allen, L.H., Black, A.K., de Mata, M., Pelto, G.H., 2002a. Diet and iron status of nonpregnant women in rural Central Mexico. The American Journal of Clinical Nutrition. PMid:12081829

View Article PubMed/NCBITorres-Maravilla, E., Lenoir, M., Mayorga-Reyes, L., Allain, T., Sokol, H., Langella, P., Sánchez-Pardo, M.E., Bermúdez-Humarán, L.G., 2016. Identification of novel anti-inflammatory probiotic strains isolated from pulque. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 100, 385-396. PMid:26476654

View Article PubMed/NCBIGonzález-Vázquez, R., Azaola-Espinosa, A., Mayorga-Reyes, L., Reyes-Nava, L.A., Shah, N.P., Rivera-Espinoza, Y., 2015. Isolation, Identification and Partial Characterization of a Lactobacillus casei Strain with Bile Salt Hydrolase Activity from Pulque. Probiotics Antimicrob. Proteins 7, 242-248. PMid:26566892

View Article PubMed/NCBITovar, L.R., Olivos, M., Gutierrez, M.E., 2008. Pulque, an alcoholic drink from rural Mexico, contains phytase. Its in vitro effects on corn tortilla. Plant Foods Hum. Nutr. 63, 189-194. PMid:18758961

View Article PubMed/NCBISanchez-Marroquin, A., Hope, P.H., 1953. Agave Juice, Fermentation and Chemical Composition Studies of Some Species. J. Agric. Food Chem. 1, 246-249.

View ArticleEscalante A, Rodríguez ME, Martínez A, López-Munguía A, Bolívar F, Gosset G, 2004. Characterization of bacterial diversity in Pulque , a traditional Mexican alcoholic fermented beverage, as determined by 16S rDNA analysis. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 235, 273-279. PMid:15183874

View Article PubMed/NCBIEscalante, A., López Soto, D.R., Velázquez Gutiérrez, J.E., Giles-Gómez, M., Bolívar, F., López-Munguía, A., 2016. Pulque, a Traditional Mexican Alcoholic Fermented Beverage: Historical, Microbiological, and Technical Aspects. Front. Microbiol. 7. PMid:27446061

View Article PubMed/NCBIIlleghems, K., De Vuyst, L., Papalexandratou, Z., Weckx, S., 2012. Phylogenetic analysis of a spontaneous cocoa bean fermentation metagenome reveals new insights into its bacterial and fungal community div[12]ersity. PLoS One 7, e38040. PMid:22666442

View Article PubMed/NCBIJung, J.Y., Lee, S.H., Kim, J.M., Park, M.S., Bae, J.-W., Hahn, Y., Madsen, E.L., Jeon, C.O., 2011. Metagenomic Analysis of Kimchi, a Traditional Korean Fermented Food. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 77, 2264-2274. PMid:21317261

View Article PubMed/NCBILyu, C., Chen, C., Ge, F., Liu, D., Zhao, S., Chen, D., 2013. A preliminary metagenomic study of puer tea during pile fermentation. J. Sci. Food Agric. 93, 3165-3174. PMid:23553377

View Article PubMed/NCBISulaimon, J., Gan, H.M., Yin, W.-F., Chan, K.-G., 2014. Microbial succession and the functional potential during the fermentation of Chinese soy sauce brine. Front. Microbiol. 5, 556. PMid:25400624

View Article PubMed/NCBIEscobar-Zepeda, A., Sanchez-Flores, A., Quirasco Baruch, M., 2016. Metagenomic analysis of a Mexican ripened cheese reveals a unique complex microbiota. Food Microbiol. 57, 116-127. PMid:27052710

View Article PubMed/NCBINalbantoglu, U., Cakar, A., Dogan, H., Abaci, N., Ustek, D., Sayood, K., Can, H., 2014. Metagenomic analysis of the microbial community in kefir grains. Food Microbiol. 41, 42-51. PMid:24750812

View Article PubMed/NCBIDublin, Ireland, Van Hoorde, K., Butler, F., 2018. Use of next‐generation sequencing in microbial risk assessment. EFSA Journal 16.

View ArticleKovac, J., den Bakker, H., Carroll, L.M., Wiedmann, M., 2017. Precision food safety: A systems approach to food safety facilitated by genomics tools. Trends Analyt. Chem. 96, 52-61.

View ArticleWylezich, C., Papa, A., Beer, M., Höper, D., 2018. A Versatile Sample Processing Workflow for Metagenomic Pathogen Detection. Sci. Rep. 8, 13108. PMid:30166611

View Article PubMed/NCBIGómez-Aldapa, C.A., Díaz-Cruz, C.A., Villarruel-López, A., Torres-Vitela, M. del R., Añorve-Morga, J., Rangel-Vargas, E., Cerna-Cortes, J.F., Vigueras-Ramírez, J.G., Castro-Rosas, J., 2011. Behavior of Salmonella Typhimurium, Staphylococcus aureus, Listeria monocytogenes, and Shigella flexneri and Shigella sonnei during production of pulque, a traditional Mexican beverage. J. Food Prot. 74, 580-587. PMid:21477472

View Article PubMed/NCBISu, X., Pan, W., Song, B., Xu, J., Ning, K., 2014. Parallel-META 2.0: enhanced metagenomic data analysis with functional annotation, high performance computing and advanced visualization. PLoS One 9, e89323. PMid:24595159

View Article PubMed/NCBIDixon, P., 2003. VEGAN, a package of R functions for community ecology. J. Veg. Sci. 14, 927.

View ArticleMcMurdie, P.J., Holmes, S., 2013. phyloseq: an R package for reproducible interactive analysis and graphics of microbiome census data. PLoS One 8, e61217. PMid:23630581

View Article PubMed/NCBIWood, D.E., Salzberg, S.L., 2014. Kraken: ultrafast metagenomic sequence classification using exact alignments. Genome Biol. 15, R46. PMid:24580807

View Article PubMed/NCBIPeng, Y., Leung, H.C.M., Yiu, S.M., Chin, F.Y.L., 2012. IDBA-UD: a de novo assembler for single-cell and metagenomic sequencing data with highly uneven depth. Bioinformatics 28, 1420-1428. PMid:22495754

View Article PubMed/NCBIZhu, W., Lomsadze, A., Borodovsky, M., 2010. Ab initio gene identification in metagenomic sequences. Nucleic Acids Res. 38, e132. PMid:20403810

View Article PubMed/NCBICamacho, C., Coulouris, G., Avagyan, V., Ma, N., Papadopoulos, J., Bealer, K., Madden, T.L., 2009. BLAST+: architecture and applications. BMC Bioinformatics 10, 421. PMid:20003500

View Article PubMed/NCBIEddy, S.R., 2011. Accelerated Profile HMM Searches. PLoS Comput. Biol. 7, e1002195. PMid:22039361

View Article PubMed/NCBIEl-Gebali, S., Mistry, J., Bateman, A., Eddy, S.R., Luciani, A., Potter, S.C., Qureshi, M., Richardson, L.J., Salazar, G.A., Smart, A., Sonnhammer, E.L.L., Hirsh, L., Paladin, L., Piovesan, D., Tosatto, S.C.E., Finn, R.D., 2018. The Pfam protein families database in 2019. Nucleic Acids Res. PMid:30357350

View Article PubMed/NCBIGrabherr, M.G., Haas, B.J., Yassour, M., Levin, J.Z., Thompson, D.A., Amit, I., Adiconis, X., Fan, L., Raychowdhury, R., Zeng, Q., Chen, Z., Mauceli, E., Hacohen, N., Gnirke, A., Rhind, N., di Palma, F., Birren, B.W., Nusbaum, C., Lindblad-Toh, K., Friedman, N., Regev, A., 2011. Full-length transcriptome assembly from RNA-Seq data without a reference genome. Nat. Biotechnol. 29, 644-652. PMid:21572440

View Article PubMed/NCBIKanehisa, M., Furumichi, M., Tanabe, M., Sato, Y., Morishima, K., 2017. KEGG: new perspectives on genomes, pathways, diseases and drugs. Nucleic Acids Res. 45, D353-D361. PMid:27899662

View Article PubMed/NCBIKanehisa, M., Sato, Y., Morishima, K., 2016. BlastKOALA and GhostKOALA: KEGG Tools for Functional Characterization of Genome and Metagenome Sequences. J. Mol. Biol. 428, 726-731. PMid:26585406

View Article PubMed/NCBIMarchler-Bauer, A., Bo, Y., Han, L., He, J., Lanczycki, C.J., Lu, S., Chitsaz, F., Derbyshire, M.K., Geer, R.C., Gonzales, N.R., Gwadz, M., Hurwitz, D.I., Lu, F., Marchler, G.H., Song, J.S., Thanki, N., Wang, Z., Yamashita, R.A., Zhang, D., Zheng, C., Geer, L.Y., Bryant, S.H., 2016. CDD/SPARCLE: functional classification of proteins via subfamily domain architectures. Nucleic Acids Res. 45, D200-D203. PMid:27899674

View Article PubMed/NCBIYang, J., Zhang, Y., 2015. Protein Structure and Function Prediction Using I-TASSER, in: Current Protocols in Bioinformatics. pp. 5.8.1-5.8.15. PMid:26678386

View Article PubMed/NCBIBehravesh CB, W.I.T., 2012. EMERGING FOODBORNE PATHOGENS AND PROBLEMS: EXPANDING PREVENTION EFFORTS BEFORE SLAUGHTER OR HARVEST, in: National Academies Press (US) (Ed.), Institute of Medicine (US). Improving Food Safety Through a One Health Approach: Workshop Summary. Institute of Medicine (US), Washington (DC), p. A14.

Gómez-Aldapa, C.A., Díaz-Cruz, C.A., Villarruel-López, A., Del Refugio Torres-Vitela, M., Rangel-Vargas, E., Castro-Rosas, J., 2012. Acid and alcohol tolerance of Escherichia coli O157:H7 in pulque, a typical Mexican beverage. Int. J. Food Microbiol. 154, 79-84. PMid:22240059

View Article PubMed/NCBILucas, T., Horton, R., 2019. The 21st-century great food transformation. The Lancet. 33179-9 https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(18)33179-9

View ArticleTakeuchi, M., Hamana, K., Hiraishi, A., 2001. Proposal of the genus Sphingomonas sensu stricto and three new genera, Sphingobium, Novosphingobium and Sphingopyxis, on the basis of phylogenetic and chemotaxonomic analyses. Int. J. Syst. Evol. Microbiol. 51, 1405-1417. PMid:11491340

View Article PubMed/NCBIDewhirst, F.E., Chen, T., Izard, J., Paster, B.J., Tanner, A.C.R., Yu, W.-H., Lakshmanan, A., Wade, W.G., 2010. The human oral microbiome. J. Bacteriol. 192, 5002-5017. PMid:20656903

View Article PubMed/NCBIWatanabe, S., Makino, K., 2009. Novel modified version of nonphosphorylated sugar metabolism--an alternative L-rhamnose pathway of Sphingomonas sp. FEBS J. 276, 1554-1567. PMid:19187228

View Article PubMed/NCBIGiles-Gómez, M., Sandoval García, J.G., Matus, V., Campos Quintana, I., Bolívar, F., Escalante, A., 2016. In vitro and in vivo probiotic assessment of Leuconostoc mesenteroides P45 isolated from pulque, a Mexican traditional alcoholic beverage. Springerplus 5, 708. PMid:27375977

View Article PubMed/NCBIBravo, J.A., Forsythe, P., Chew, M.V., Escaravage, E., Savignac, H.M., Dinan, T.G., Bienenstock, J., Cryan, J.F., 2011. Ingestion of Lactobacillus strain regulates emotional behavior and central GABA receptor expression in a mouse via the vagus nerve. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 108, 16050-16055. PMid:21876150

View Article PubMed/NCBIEscalante, A., Giles-Gómez, M., Flores, G., Acuña, V., Moreno-Terrazas, R., López-Munguía, A., Lappe-Oliveras, P., 2012. Pulque Fermentation, in: Handbook of Plant-Based Fermented Food and Beverage Technology, Second Edition. pp. 691-706.

View ArticleScopes, R.K., Griffiths-Smith, K., 1986. Fermentation capabilities of Zymomonas mobilis glycolytic enzymes. Biotechnol. Lett. 8, 653-656.

View ArticleAlfenore, S., Molina-Jouve, C., Guillouet, S.E., Uribelarrea, J.-L., Goma, G., Benbadis, L., 2002. Improving ethanol production and viability of Saccharomyces cerevisiae by a vitamin feeding strategy during fed-batch process. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 60, 67-72.

Montañez, J.L., Victoria, J.C., Flores, R., Vivar, M.Á., 2011. Fermentation of Agave tequilana Weber Azul fructans by Zymomonas mobilis and Sacchamomyces cerevisiae in the production of bioethanol. Inf. tecnol. 22, 3-14.

View ArticleConway, T., Sewell, G.W., Osman, Y.A., Ingram, L.O., 1987. Cloning and sequencing of the alcohol dehydrogenase II gene from Zymomonas mobilis. J. Bacteriol. 169, 2591-2597. PMid:3584063

View Article PubMed/NCBIKolida, S., Gibson, G.R., 2007. Prebiotic capacity of inulin-type fructans. J. Nutr. 137, 2503S-2506S. PMid:17951493

View Article PubMed/NCBISarbini, S.R., Kolida, S., Deaville, E.R., Gibson, G.R., Rastall, R.A., 2014. Potential of novel dextran oligosaccharides as prebiotics for obesity management through in vitro experimentation. Br. J. Nutr. 112, 1303-1314. PMid:25196744

View Article PubMed/NCBIBackstrand, J.R., Allen, L.H., Black, A.K., de Mata, M., Pelto, G.H., 2002b. Diet and iron status of nonpregnant women in rural Central Mexico. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 76, 156-164. PMid:12081829

View Article PubMed/NCBILaiño, J.E., de Giori, G.S., LeBlanc, J.G., 2013. Folate Production by Lactic Acid Bacteria, in: Bioactive Food as Dietary Interventions for Liver and Gastrointestinal Disease. pp. 251-270.

View ArticleMangels, R., Messina, V., Messina, M., 2011. The Dietitian's Guide to Vegetarian Diets. Jones & Bartlett Learning.

LeBlanc, J.G., Milani, C., de Giori, G.S., Sesma, F., van Sinderen, D., Ventura, M., 2013. Bacteria as vitamin suppliers to their host: a gut microbiota perspective. Curr. Opin. Biotechnol. 24, 160-168. PMid:22940212

View Article PubMed/NCBIAnderson, R.K., Calvo, J., 1946. A study of the nutritional status and food habits of Otomi Indians in the Mezquital Valley of Mexico. Am. J. Public Health Nations. Health 36, 883-903.

View ArticleLappe-Oliveras, P., Moreno-Terrazas, R., Arrizón-Gaviño, J., Herrera-Suárez, T., García-Mendoza, A., Gschaedler-Mathis, A., 2008. Yeasts associated with the production of Mexican alcoholic nondistilled and distilled Agave beverages. FEMS Yeast Res. 8, 1037-1052. PMid:18759745

View Article PubMed/NCBICravioto, B.R., Lockhart, E.E., Miranda, F.P., Harris, R.S., 1945. Contenido nutritivo de ciertos típicos alimentos mexicanos [nutrient content of typical Mexican foods]. Bol. Of. Sanit. Panam. 24 , 685-695.

Chellapandian, M., Larios, C., Sanchez-Gonzalez, M., Lopez-Munguia, A., 1998. Production and properties of a dextransucrase from Leuconostoc mesenteroides IBT-PQ isolated from "pulque", a traditional Aztec alcoholic beverage. J. Ind. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 21, 51-56.

View ArticleArgüello-Morales, M.A., Remaud-Simeon, M., Pizzut, S., Sarçabal, P., Willemot, R., Monsan, P., 2000. Sequence analysis of the gene encoding alternansucrase, a sucrose glucosyltransferase from Leuconostoc mesenteroides NRRL B-1355. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 182, 81-85. 00572-8

View ArticleOlivares-Illana, V., López-Munguía, A., Olvera, C., 2003. Molecular characterization of inulosucrase from Leuconostoc citreum: a fructosyltransferase within a glucosyltransferase. J. Bacteriol. 185, 3606-3612. PMid:12775698

View Article PubMed/NCBINishino, H., 1972. Biogenesis of cocarboxylase in Escherichia coli. Partial purification and some properties of thiamine monophosphate kinase. J. Biochem. 72, 1093-1100. PMid:4567662

View Article PubMed/NCBIZhang, S., Sanyal, I., Bulboaca, G.H., Rich, A., Flint, D.H., 1994. The gene for biotin synthase from Saccharomyces cerevisiae: cloning, sequencing, and complementation of Escherichia coli strains lacking biotin synthase. Arch. Biochem. Biophys. 309, 29-35. PMid:8117110

View Article PubMed/NCBIKupke, T., 2002. Molecular characterization of the 4'-phosphopantothenoylcysteine synthetase domain of bacterial dfp flavoproteins. J. Biol. Chem. 277, 36137-36145. PMid:12140293

View Article PubMed/NCBIMccormick, D.B., Gregory, M.E., Snell, E.E., 1961. Pyridoxal phosphokinases. I. Assay, distribution, I. Assay, distribution, purification, and properties. J. Biol. Chem. 236, 2076-2084.

Plaut, G.W.E., Harvey, R.A., 1971. [157] The enzymatic synthesis of riboflavin, in: Methods in Enzymology. pp. 515-538. 18114-1

View ArticleSchnell, J.R., Jane Dyson, H., Wright, P.E., 2004. Structure, Dynamics, and Catalytic Function of Dihydrofolate Reductase. Annu. Rev. Biophys. Biomol. Struct. 33, 119-140. PMid:15139807

View Article PubMed/NCBIWarren, M.J., Raux, E., Schubert, H.L., Escalante-Semerena, J.C., 2002. The biosynthesis of adenosylcobalamin (vitamin B12). Nat. Prod. Rep. 19, 390-412. PMid:12195810

View Article PubMed/NCBIGoodlove, P.E., Cunningham, P.R., Parker, J., Clark, D.P., 1989. Cloning and sequence analysis of the fermentative alcohol-dehydrogenase-encoding gene of Escherichia coli. Gene 85, 209-214. 90483-6

View ArticleMadern, D., 2002. Molecular evolution within the L-malate and L-lactate dehydrogenase super-family. J. Mol. Evol. 54, 825-840. PMid:12029364

View Article PubMed/NCBIBrocker, C., Lassen, N., Estey, T., Pappa, A., Cantore, M., Orlova, V.V., Chavakis, T., Kavanagh, K.L., Oppermann, U., Vasiliou, V., 2010. Aldehyde dehydrogenase 7A1 (ALDH7A1) is a novel enzyme involved in cellular defense against hyperosmotic stress. J. Biol. Chem. 285, 18452-18463. PMid:20207735

View Article PubMed/NCBIvan Hijum, S.A.F.T., Kralj, S., Ozimek, L.K., Dijkhuizen, L., van Geel-Schutten, I.G.H., 2006. Structure-function relationships of glucansucrase and fructansucrase enzymes from lactic acid bacteria. Microbiol. Mol. Biol. Rev. 70, 157-176. PMid:16524921

View Article PubMed/NCBIPereira, Y., Petit-Glatron, M.F., Chambert, R., 2001. yveB, Encoding endolevanase LevB, is part of the sacB-yveB-yveA levansucrase tricistronic operon in Bacillus subtilis. Microbiology 147, 3413-3419. PMid:11739774

View Article PubMed/NCBIGozu, Y., Ishizaki, Y., Hosoyama, Y., Miyazaki, T., Nishikawa, A., Tonozuka, T., 2016. A glycoside hydrolase family 31 dextranase with high transglucosylation activity from Flavobacterium johnsoniae. Biosci. Biotechnol. Biochem. 80, 1562-1567. PMid:27170214

View Article PubMed/NCBIFouet, A., Klier, A., Rapoport, G., 1986. Nucleotide sequence of the sucrase gene of Bacillus subtilis. Gene 45, 221-225. 90258-1

View Article